GÖRLITZ: The border of populism

German populist nationalism and Polish liberalism meet along the border

Görlitz is a beautiful central European city. Its old centre miraculously escaped significant damage during the war and its delightful, picturesque streets are often used by film crews as locations for period dramas such as Grand Budapest Hotel because it is so complete: ‘Görliwood’. It was preserved by the DDR authorities insofar as its centre was not scarred by demolitions, roads or concrete monstrosities, but not much was invested and it has taken the support of reunified Germany and the European Union to burnish this jewel back into what it should be.

The centre of beautiful Görlitz

Görlitz is now on the edge of Germany. The old town and the station are on the German side, while a small stretch of riverside buildings and some newer suburbs have formed the Polish town of Zgorzelec since 1945. It is where the treaty ratifying the Oder-Neisse frontier was signed by representatives of Poland and the DDR in 1950. German Görlitz is in the tiny section of the post-1815 Prussian province of Silesia which remains in Germany (though it was not in pre-1740 Silesia) and it is the nerve-ending that twitches the ghostly pains of an amputated limb. The city was transferred from Saxony to Prussia at the Congress of Vienna but before 1635 was under the Bohemian crown; this part of the world has layers of Bohemian German and Polish cultural and architectural history that makes so much nationalist chest-beating seem embarrassingly simplistic.

View from Polish Zgorzelec to German Görlitz across the Neisse, LSB Oct 2019

Since Polish accession to Schengen the border controls between German Görlitz and Polish Zgorzelec have disappeared. A new pedestrian bridge spans the Neisse in the heart of the Old Town, watched over not by border guards but by a webcam installed on the side of Gorlitz’s fine church. I freely admit that when I first came here in 2011 I wandered back and forward over the bridge between Poland and Germany and called Hannah to make sure she could see me standing there, in the middle of this central European bridge, from her desk in London.

(Webcam picture from Gorlitz-Zgorzelec old town bridge, February 2011, LSB standing dead centre)

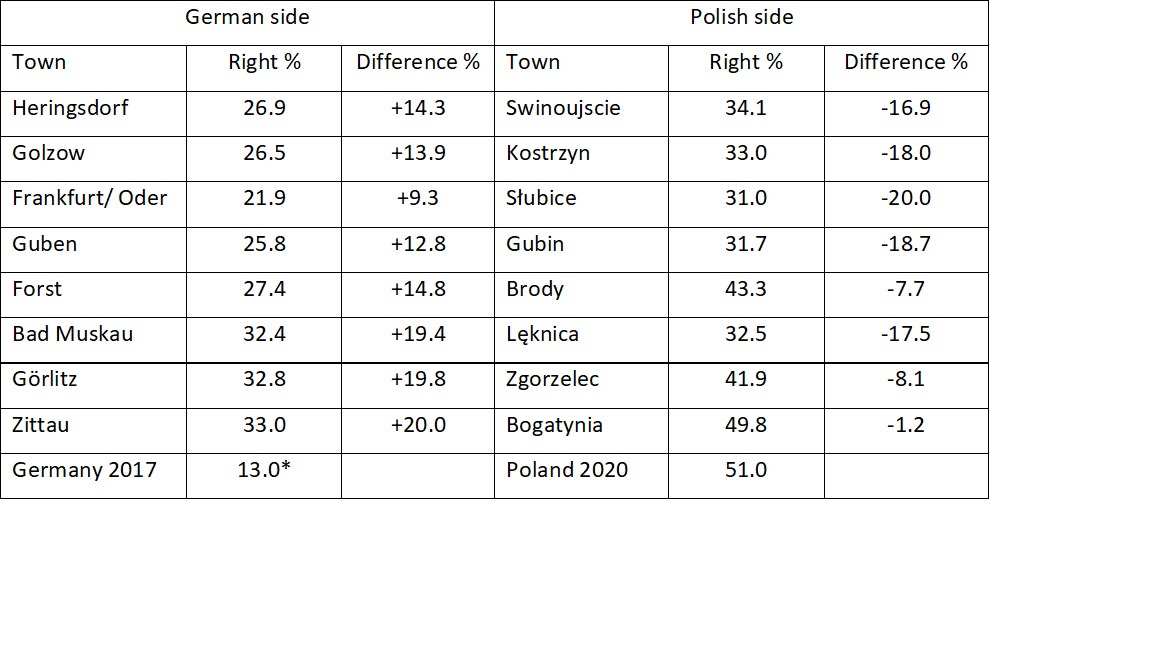

Eastern Saxony was known in the later years of the DDR as the Valley of the Clueless, an allusion to the fact that West German television broadcasts did not reach the area and its residents depended on East German state television for their information. It is still a politically distinctive region within Germany, but it is now a hotbed of support for the anti-immigrant right wing. The PEGIDA movement started on the streets of Dresden, despite the minimal number of Muslims in the area and the central place hostility to Islam had in PEGIDA ideology. In the 2017 election, when the anti-immigration Allianz für Deutschland (AfD) made its national electoral breakthrough, its strongest support was in the borderland along the Neisse. Nearly a third of voters in the corner of eastern Saxony that backs onto the Neisse voted for the far right, while it was more like a quarter in the towns along the Oder and Neisse in Brandenburg. In Germany as a whole the AfD scored 12.6 per cent, so all of these places were hotbeds of German nationalism compared to the country as a whole.

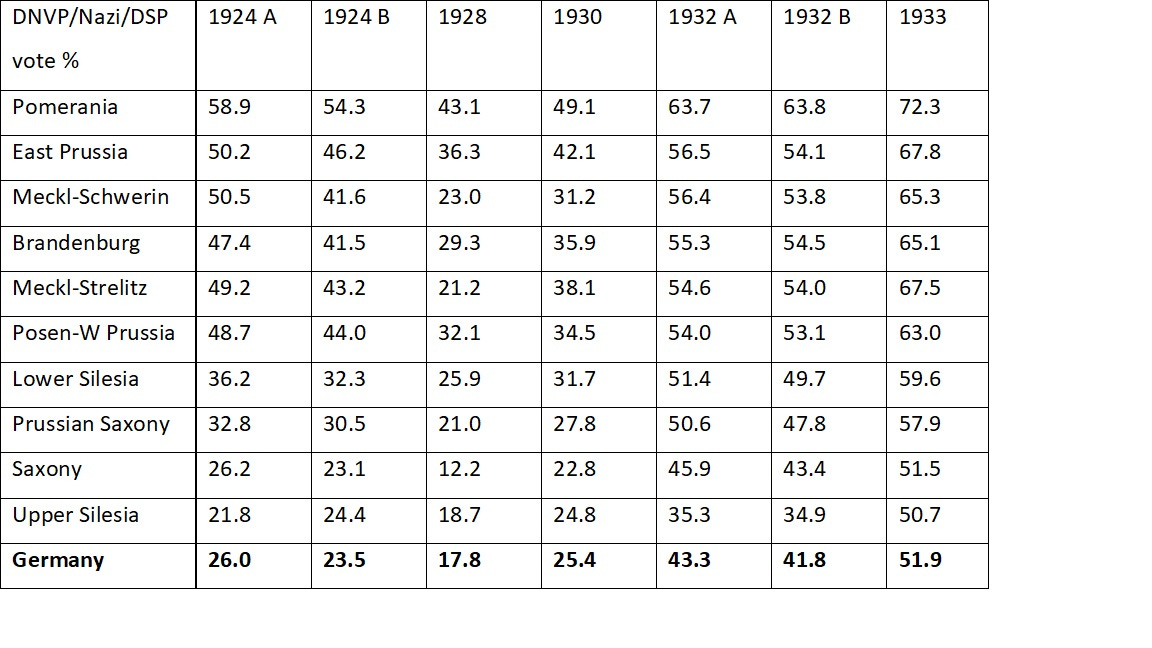

This fits into a long historical pattern.[1] Every far-right party in German electoral history, from the Empire to the unified republic, has had its strongholds in eastern Germany. During the Weimar Republic, eastern Germany outside the big cities was the most enthusiastic region of the country when it came to voting for extreme nationalism – before 1930 the DVNP (German National People’s Party) and after that point for the NSDAP (National Socialists). Part of this, particularly in Lower Silesia and along the Baltic, was because of its social structure – it happened to be full of the sort of groups such as impoverished small farmers and artisans that flocked to those parties, and – other than Silesia – without many industrial workers and Catholics who were the most resistant. But there was more to it than that. It was infected with the border psychosis that had been blowing in from the east, the depopulation, the fear the feeling of emptiness, the feeling of pressing competition from other ethnic groups. Ironically, eastern Germany had extreme nationalism for some of the same reasons that extreme forms of Slavic nationalism gained support. It was still, unlike neighbouring Posen, defensibly German but it was becoming chilly. The idea of eastern conquest, pushing the border well away from the beaches of Pomerania or the fields of Silesia, had its appeal even though it backfired on a truly grand scale. It is still true that the German far east is more susceptible to ‘eastern’ style nationalism than the rest of the country which has had a painful lesson in civic nationalism.

Voting for the far right in eastern Germany, 1924-33

Part of the reason why the western allies were prepared to see eastern Germany so ruthlessly treated in 1945 was the perception that it was that part of the country that historically embodied Germany’s dark side, with its ‘Prussian militarism’ and its arrogant Junkers. Some western Germans also shared the idea that the bad Germany could be exorcised by amputating the east; the Rhineland Christian Democrat and first Chancellor of the Federal Republic, Konrad Adenauer, was reputed to draw the blinds on his train carriage when he crossed the Elbe to avoid seeing the unnerving landscape of ‘Asia’ from the window. The Allies ensured that ‘Prussia’ was wiped from the map in 1947.

I was intrigued to compare the rise of the hard right in eastern Germany with what was happening on the other side of the border in the far west of Poland, where economic conditions might be expected to be pretty similar. I found that by contrast it was relatively poor territory for the parties of the Polish right – the establishment social-conservative PiS (which has become a more radical authoritarian party while in office), the populist Kukis’15 party and the reactionary provocateurs of the KORWIN party. As well as looking at the nationalism of eastern Germany’s border zone, it’s worth considering why crossing the river puts you in in a particularly liberal part of Poland, particularly as the western border strip only contains one large city (Szczecin).

Right %: In Germany, the vote share in the 2017 election for the AfD plus where available the NPD; in Poland, the second-round vote for Duda in the 2020 Presidential election.

Difference %: the gap between the local share for the right and the national share, i.e. 12.6 per cent for the AfD and 13.0 per cent for AfD and NPD combined, 51.0 per cent for the combined votes of PiS, Kukis15 and KORWIN.

The right wing started weaker on average in the western border towns of Poland and, against the national trend, became weaker in the elections of October 2019 and did poorly in the presidential election of 2020 - and of course the parliamentary elections of 2023. Part of the reason for the difference on the Polish side is that the economic circumstances are not as similar as one might expect.[2] Western Polish towns have been successful at attracting inward investment; it is near the comfort zone and home markets for German firms in particular, but with lower costs and sometimes development incentives, the same formula that has made western Slovakia an economic success story. Quality jobs attract a young, educated population more similar to the Polish diaspora in the west than the left behind further east. Rafał Gronicz, mayor of Zgorzelec since 2006, sees investment like that from Siemens in his city as ‘a great success for me [because we attract well-educated people with a high income. To attract that kind of people is a success for the city. These people are most likely young.’ [3]

Although Gronicz is keen on international co-operation across the border, it does not attract all that much interest even among the young European-minded Poles of Zgorzelec, just across the river from the attractive German city of Görlitz. Gronicz speaks of integration with Germany ‘from below’ – that states can create structures but when wanted people will build the deeper links organically by their own actions. There has been a long period of the barriers being kept high even between the DDR and Poland, and defensiveness of anything that felt like a German claim on the city. The split city is perhaps less of a single unit than Frankfurt-Słubice (‘Slubfurt’) or Gubin- Guben downriver, but it is not for want of good official relations between the two. The city government on the German side was held by the CDU candidate Octavian Ursu after a tough contest against the AfD in June 2019.

The border at Zgorzelec therefore has two political faces - a self-confident Polish liberalism on one side and the German centre-right under pressure from the extreme right on the other. It is one of the more paradoxical borders, although the same pattern can be found for instance around Oradea near the Romanian-Hungarian frontier. The problems on the German side are even more acute at the small town of Ostritz, but to read about that you’ll have to wait for the book Borderlines, due out in June 2024.

[1] James Hawes for Handelsblatt ‘Politically East and West Germany will never match’ 8 December 2017. https://global.handelsblatt.com/opinion/politically-east-and-west-germany-will-never-match-862927

[2] The grimmest small town I have visited on the Polish side of the Oder-Neisse line is Przewosz (Priebus in German times) – a depopulated, down-at-heel little place with the majority of people on the downtown streets being aimless alcoholics. The Przewosz district is an island of right wing support along the border.

[3]https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=tfbOCwAAQBAJ&pg=PA127&lpg=PA127&dq=mayor+of+zgorzelec&source=bl&ots=Wty8vXY2dz&sig=5KDaxJPKlis18JQMtICfhaUNwXQ&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwiIne2Jw-zeAhXkJ8AKHTPKDvkQ6AEwAnoECAAQAQ#v=onepage&q&f=false